There is NO SUCH THING as a Family Coat of Arms

Elizabeth E. Bullard

August 17, 2012

This original article may not be reproduced in any manner

without the express written consent of the author.

Jump to Section:

Granting the Right to Bear Arms

Locating a Coat of Arms for Your Ancestor

Locating a Coat of Arms for Your Family Name

The Actual Coat of Arms Design (illustrated)

There Is No Such Thing

I see it all of the time: people asking about their family’s coat of arms or family crest. Let’s get one thing straight right away: There is no such thing.

The general misunderstanding about a “family crest” and a “family coat of arms” may have arisen from an abbreviation of the terminology in heraldry for an important part of a coat of arms. Additionally, since there is no regulation for bearing a coat of arms in most countries, including the United States, there has been a proliferation of companies that offer to find your “family coat of arms” and “family crest” and then supply you with a “family history”. While there is no reason that you should not be able to enjoy the decoration of a coat of arms that is associated with someone who lived centuries ago and who shared your surname, you must be aware that it is nothing more than a decoration – it probably has no significance whatsoever to your relationship with an actual ancestor. Any company that purports to be able to provide you with a coat of arms and family history, based only on your family name, is conducting a scam.

Crest and Coat of Arms

First, let’s look at the difference between a coat of arms and a crest. Fairbairn’s Book of Crests of the Families of Great Britain and Ireland, first published in 1859 and revised over the years in various reprints, is one of the most highly-respected sources of heraldry information. The term “crest” has become synonymous with the term “coat of arms”, since one is part of the other. Over time, the “crest” has become associated with family names, independent of the coat of arms, in publications such as Fairbairn’s. Beginning in the 19th century, the crest that appeared on top of the helm in a coat of arms was mistakenly dubbed a "family crest" by some individuals and since has become an inaccurate synonym for a full coat of arms. The crest part of a coat of arms (the part that appears above the image of the helm) has been used on engravings, rings, bookplates and other means of displaying heritage for years. Gaelic tradition actually allows family members to use the crest part of a coat of arms on badges (a circular belt), thus allowing all members of a given clan the entitlement to use a clan badge. Other than that exception, however, crests never were intended to be used separately from an official coat of arms.

Many people throughout history have used coats of arms ornamentally without giving much thought to the accuracy of their designs or their own right to use them. The need for a coat of arms arose in about the 12th century, around the time of the Crusades. The purpose of a coat of arms was so that a knight, dressed in armor from head to toe, could be recognized by friends and by enemies. Since most knights could not be distinguished from one another by their armor alone, a new method of identification became necessary. This necessity resulted in the idea that, if special markings were painted on the knight’s shield (the largest piece of equipment carried by a knight), anyone would be able to distinguish one knight from another from a distance. These shield markings also were embroidered on the tunic worn by a knight over his armor and on the uniforms worn by the servants of the knight’s household. The tunics were “coats”. A knight’s shield and tunic markings usually were granted to him once he became entitled to bear arms, hence the term “coat of arms”. The coats of arms began with a fairly simple design. Subsequent generations often made slight variations to the design in order to make it their own. Marriages often resulted in the combination of two different coats of arms.

Except for a few rare exceptions, there is no such thing as a coat of arms for a surname in general, despite the claims and implications of some companies to the contrary. A coat of arms was not awarded to a family or to a family name. Instead, a coat of arms was awarded to an individual who was entitled to bear arms on behalf of his ruler. For example, while a specific coat of arms and crest may have been awarded to an individual that carried my ancient English family surname, Bullard or Bulward, there never would have been a single coat of arms granted to every man in his family. In England, you must be able to prove direct blood descent in order to have the legal right to bear an ancestor’s coat of arms. In other words, if I could prove a direct blood tie to an English knight named Bullard or Bulward, who was awarded a specific coat of arms, my father and my brothers would be entitled to bear that knight’s coat of arms. Coats of arms are a form of property and may rightfully be used only by the uninterrupted male line descendants of the person to whom the coat of arms was originally granted. Such grants were (and are) made by the proper heraldic authority for the country in question.

Granting the Right to Bear Arms

The Law of Arms governs the bearing of arms. The bearing of arms is the possession, use, or display of arms, also called coats of arms, coat armour, or armorial bearings. The officials who grant coats of arms are called pursuivants, heralds, or kings of arms. The Law of Arms dictates that coats of arms may be borne only by virtue of ancestral right or by a grant made under due authority. Ancestral right means descent from an ancestor who lawfully bore arms through an all-male line. Since medieval times, due authority has been the Crown or the State. The College of Arms maintains the official registry for all coats of arms in England and Wales. Other countries allow the registration of coats of arms, but make no official restrictions on the bearing of arms.

In England and Wales, a grant of arms confers certain rights upon the grantee and his or her heirs. According to law, no person lawfully may bear the same coat of arms as another person in the same heraldic jurisdiction. In Ireland, the cultural tradition of granting of arms is allowed through the Office of the Chief Herald of Ireland. Established under the English Crown in 1552 as the Ulster King of Arms, this office was renamed after the 1938 Constitution of Ireland. In Scotland, as opposed to England, the Law of Arms is a branch of civil law. The misappropriation of arms considered a crime, actionable under the common law of Scotland. The Laws of Arms in British Commonwealth realms, such as Australia, New Zealand and other realms of the Queen, is derived from the laws of England. The Canadian Laws of Arms currently is regulated by the Canadian Heraldic Authority, but the laws themselves otherwise are derived from the laws of England.

In Denmark, non-official coats of arms are not protected, except by copyright law. There is no official heraldic authority in Denmark. In Norway, the National Archives is the heraldic authority of municipal arms. In Germany, the right to arms is passed by ancestral right through the male line. The right to arms is recorded, published and protected under civil law. In Italy, there is no formal system for recording cadency outside of the House of Savoy. There has been no official regulation coats of arms and titles of nobility in Italy since the abolition of the Consulta Araldica in 1948. Before 1948, the Consulta Araldica primarily focused on titles of nobility, rather than heraldry. Before about 1800, Italy focused more on feudal rights and actual grants of arms were very rare.

In South Africa, all citizens have the right to bear arms, provided that they do not infringe on the rights of other citizens. The Bureau of Heraldry registers coats of arms and protects them from misuse. In the United States, coats of arms are protected for specific units of its armed forces, with few exceptions. Though he used his own ancestral arms, George Washington openly opposed to the establishment of a national heraldic authority. Blazons are not protected in any way in the United States.

Several other countries have a Law of Arms, but most of them are not well-regulated. Those laws vary from country to country and are based, in general, on the laws in British Commonwealth realms.

Inheritance of Coats of Arms

By custom during the middle ages, and later by law through granting authorities, an individual coat of arms belonged to one man only, being passed from him to his male-line descendants after his death. As I have already discussed, there is, therefore, no such thing as a particular coat of arms for a general surname. Because of this descent of coats of arms through families, heraldry is very important to genealogists, providing evidence of family relationships. There are three methods by which a coat of arms might be carried from one generation to the next:

Cadency: A knight is granted a coat of arms. While he is alive, his four sons each inherit their paternal shield. All of them alter the shield design slightly – a change that, in theory, will be perpetuated by their own branches of the family by male descendants. The eldest son follows this tradition along with his brothers. In this family example, we now have one coat of arms with five slightly different shield displays. When the knight dies, his eldest son will revert back to the original coat of arms, so that it may be passed, unaltered, to future generations of male descendants.

Marshalling: An unmarried knight is granted a coat of arms. He marries a woman whose father also bears a coat of arms. The knight may then merge or combine the two coats of arms in a practice known as marshaling – the act of combining the designs of more than one coat of arms on a shield, which denotes the alliance of two families. Common methods of marshalling included impaling (placing the arms of the husband side by side on the shield with the arms of the wife’s father), escutcheon of pretense (placing the arms of the wife’s father on a small shield in the center of the husband’s shield) and quartering (placing the husband’s arms in the first and fourth quarters of the shield and the arms of the wife’s father in the second and third quarters of the shield). Quartering also was a method used by children to display the arms of their parents (the father’s arms in the first and fourth quarters of the shield and the maternal grandfather’s arms in the second and third quarters of the shield).

Women Bearing Arms: Women were not excluded from the right to bear their father’s arms. In fact, women always have been allowed to inherit arms from their fathers and to receive grants of coats of arms. However, women may only pass inherited arms to their children if they have no brothers, making them heraldic heiresses. For example, a knight is granted a coat of arms. He fathers four sons and two daughters. All of the knight’s children will inherit his coat of arms. However, only the knight’s sons will be allowed to pass the coat of arms to their children. All of the sons will practice cadency until the death of their father, at which time the eldest son will revert to his father’s original shield. The daughters will not practice cadency, but their father’s arms may be added to their husbands’ coats of arms by marshalling. If all of the knight’s sons die before they father children, the daughters will be eligible to pass their father’s original coat of arms to their sons, provided that those sons have the right to bear arms. The eldest grandson will bear the original shield and the other grandsons will practice cadency. Since most women did not wear armor during the Middle Ages, convention warranted the display of a father’s coat of arms in a lozenge-shaped (diamond-shaped) field, rather than on a shield, if she was unmarried or widowed. Once married, a woman was entitled to bear the shield of her husband, upon which her father’s arms usually would have been marshalled.

Locating a Coat of Arms for Your Ancestor

Further complicating the issue of who bore which coat of arms is that the only authoritative source information for most coats of arms lists only a city and/or county of origin in ancient geographic regions and sometimes only the country of origin was listed. That is why, unless you can prove direct blood descent from a particular individual who bore a coat of arms, the best that you can hope to find is the oldest coat of arms that was granted to someone with a particular surname in a given region. If you can prove direct blood descent from a specific ancient ancestor, you may contact the College of Arms in the country of that ancestor’s nativity or citizenship. For a fee, the College of Arms will search its records to verify whether or not a coat of arms was awarded to your ancestor.

Locating a Coat of Arms for Your Family Name

The next time that you come across a coffee mug or other product with a “family coat of arms” for your surname, remember that just because your surname happens to be Smith, it doesn’t give you the right to any of the hundreds of coats of arms borne by other individuals named Smith throughout history. How could anyone that has not researched your direct family line know whether you have inherited the right to display a particular coat of arms? The likelihood that you will locate a real coat of arms, based on your family name alone, is nil. Why? Because family coats of arms simply do not exist.

The Actual Coat of Arms Design

The official, written description of a coat of arms is called the “blazon of arms”. The blazon is a system of recording particular words that denote metal, colors, placement and styling. As far a design, the blazon does not dictate specific styles and the actual designs are based more upon the herald’s or artist’s preferences. Mantles and helms, as well as banners and mottos, are not official elements of the blazon of arms. Reading blazon of arms really is like reading a foreign language. Examples of a blazon of arms are:

Image above: The arms of the University of Cambridge, granted 1573 by Robert Cooke, Clarenceux King of Arms

The blazon is "Gules a cross ermine between four lions passant gardant or and on the cross a closed book fessways gules clasped and garnished gold, the clasps downward".

The original blazon was "Gules sur ung croix dermines entre quatre Lions passant d'or Livre de gules".

The blazon means: On a red background (gules), a white cross with black ermine tails (ermine) between four yellow (or) lions walking but with one leg raised (passant) and facing the observer (gardant). On the center of the cross is a closed red (gules) book with its spine horizontal (fessways) with gold clasps pointed downward.

Image above: The arms of the Victoria University of Manchester, granted to its predecessor, Owen's College, 14 Oct 1871

The blazon is "Argent, a serpent nowed vert on a chief nebulee azure, a sun issuant or".

The blazon means: The shield is white (argent) and shows a green (vert) snake (serpent) in the form of a knot (nowed). The top third (chief) is blue (azure) and separated from the rest of the shield by a line which has cloud-shaped waves in it (nebulee). A yellow (or) sun is emerging from the dividing line (issuant).

Image above: The arms of the University of Nottingham, granted to its predecessor, University College, 1904

The blazon is "Barry wavy of six argent and azure, a cross moline gules, on a chief of the last an open book proper clasped or inscribed with the words 'Quaerenti Ostium' in Roman characters sable between two domed towers also proper, that to the dexter ensigned with an increscent of the first and that to the sinister with an estoile also or".

The blazon means: The shield has six horizontal lines (barry) alternatively white (argent) and blue (azure) and which are wavy. On them is a red (gules) cross of which the arms don't reach the edge of the shield but which are flared in a certain conventional manner (moline). Above the main part of the shield is a red (gules) horizontal stripe (chief) on which are a book showing the words 'Quaerenti Ostium' between two capped (domed) towers in their natural colors (proper). The tower to the right (dexter) {"right" is from the perspective of standing behind the shield} is topped (ensigned) with a white (argent) crescent (increscent) and the tower to the left (sinister) {again, the perpective is from behind the shield} with a yellow (or) star with six rays (estoile). "Quaerenti Ostium", roughly translated, means "door for the searching", as in the door for people in search of the truth or knowledge.

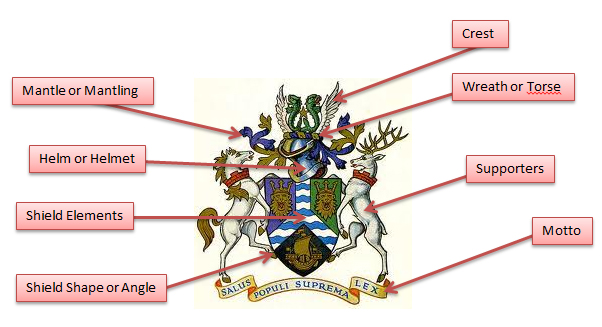

The image above is of a full and decorative coat of arms. Breaking down the pieces, beginning at the top, are the following elements:

The crest was incorporated by many nobles and knights around the end of the 13th century. It appeared above the shield and would have been a part of an official blazon, though not every coat of arms included it. It typically was made of feathers, leather, or wood and was used to help distinguish the helm, similar to the devices on the shield.

The wreath, or torse, would not have been a part of an official blazon. It was a twisted silken scarf that covered the joint where the crest was attached to the helm. On coats of arms, the wreath was drawn to resemble two colored scarves braided together, usually with six parts showing that incorporated the color of the first two colors named in the official blazon.

The mantle, or mantling, would not have been a part of an official blazon (though, sometimes the colors were specified) and usually incorporated two colors. The mantle represented the cloth that hung from the wreath and draped from the helm to protect the back of the head and neck from the heat of the sun and to ward off rain, though often coat of arms mantles appear to look more like the leaves of a plant. Designs varied, depending upon the herald’s or artist’s preference.

The helm, or helmet, appeared above the shield, sometimes in profile and sometime in full-faced position. The helm would not have been a part of an official blazon and rarely was identified as a particular type. The design of the helm varied with the bearer’s rank, the time period, or the herald’s or artist’s preference. A gold full-faced helm represented royalty, for example, while a steel helm with a closed visor represented a gentleman.

The shield shapes and angles would not have been parts of an official blazon and varied through the centuries, depending upon geographical origin, time period and the herald’s or artist’s preference.

The shield elements would have been a part of an official blazon, which described what designs appeared on the shield, their colors and their placement on the shield. The shield part of the coat of arms was the most important and also was the primary method by which friends and enemies identified a knight, as it was ornamented with various devices, such as unique colors and charges (animals, fish, trees and other symbols).

The supporters, usually two animals or people that were positioned on both sides of the shield, would have been a part of an official blazon. Not every coat of arms included supporters.

The motto was not granted officially with a coat of arms. Mottos were the phrase that most incorporated the basic philosophy of the family or an ancient war cry. The motto may or may not have been present on an individual coat of arms, depending upon the herald’s or artist’s preference, and normally were placed below the shield, though some occasionally appeared above the crest.